Heraklion

Minoan Heraklion

During the Minoan (prehistoric) period, there must have been a few scattered houses in what is now the center of Heraklion, with a few small communities on the neighboring hills. The area east of Heraklion, i.e. Poros, Katsambas, Alikarnassos and the airport as far as the River Karteros and Amnissos, shows early signs of habitation. It was a good place to live, due to its geomorphology and because it was the natural port of Knossos, via the River Kairatos which reaches the sea at Katsambas (the east end of the modern Heraklion harbour). This has been demonstrated by a recent excavation in the Katsambas area, which has brought part of the Minoan harbour installation to light.

The area west of the city, however (Giofyros - Ammoudara), was unsuitable for habitation because it was mostly marshy, being at the mouths of four rivers.

Archaeological evidence shows that the settlement named Heraklion probably arose during the first millennium BC (9th century BC), in the area between Daidalou and Epimendou Streets, i.e. at the top of the hill on which the centre of Heraklion now stands.

The name Heraklion

Concerning the name “Heraklion”, according to mythology Rhea, the mother of Zeus, entrusted the Curetes with guarding her newborn son, in an attempt to conceal him from his father, Cronus.

One of the Dactyls, the Idaean Herakles or Hercules (not to be confused with the famous hero of the Twelve Labours), went to Olympia, where he and his brothers (Paeonaeos, Epimedes, Iassius and Idas) organised the first footrace in the world. The Idaean Herakles crowned the victor with the branch of an olive tree he had planted there himself. This was the origin of the custom of crowning Olympic winners with olive.

Later Clysmenes, a descendant of the Idaean Herakles, founded the Olympic Games and built an altar to his forebears on the site of ancient Olympia. Heraklion is named after the Idaean Herakles.

The above myth may be intended to show that Minoan Crete was the birthplace of athletics. We know from archaeological finds and fragments of frescoes from Knossos that the Minoans loved sports, including gymnastics, archery, chariot racing, boxing, wrestling and swimming. Other, special events such as the tavrokathapsia (bull-leaping) were held at festivals.

Byzantine Heraklion - Kastro

During the First Byzantine period (4th-9th c. AD), the small town of Heraklion was known as Katsro (Castle), indicating that there was some sort of fortification. Crete was a province of the Byzantine Empire, whose capital was Constantinople. The administrative, military and religious centre of the island was Gortys. The towns of northern Crete were less developed, as the sea routes ran past the south coast.

Historians refer to the 7th and 8th centuries as “dark ages”, due to the almost total lack of information on the period from written or other sources. There are some references to natural disasters and, particularly from the mid-7th century onwards, pirate raids. These meant that the towns declined into villages, the population dwindled and the military forces on the island were reduced.

Heraklion falls to the Arabs - Chandax or Candia

A band of Saracen Arabs led by Abu Hafs Omar were driven first from Spain and then from Alexandria. Taking advantage of the weak defences of Crete, they conquered the island in 824-828 AD. Piracy was their main occupation, so they chose Heraklion as the capital of their emirate. Its position in north central Crete lent itself to their raids on the Aegean coasts on the one hand, and to the collection of agricultural produce from the whole island for trading with Islamic states on the other.

Heraklion was fortified with brick walls set on stone foundations, surrounded by a deep ditch or dry moat (khandaq), whence its new name Rabdh el Khandaq, meaning Fortress of the Ditch. This became Chandakas in Greek and Candia in Latin. Arab Chandax must have been very similar in shape to the Byzantine and Venetian town.

The Byzantine recovery of Heraklion - Megalo Kastro

Byzantine Heraklion compared to Venetian Heraklion

The Byzantines regarded Crete and its capital, Chandax, under Arab rule as a nest of pirates and slavers. Arab sources, on the contrary, state that the Arabs developed their own culture in their new territory, with Chandax as its intellectual centre. They minted their own coinage and had advanced metallurgy and pottery.

The Byzantine Empire made repeated attempts to recover Crete, its strategic location making it the key to control of the sea routes of the southern Mediterranean. In 961 AD, Nicephorus Phocas, commander-in-chief and later emperor of Byzantium, succeeded in reconquering Crete and the Second Byzantine period began.

Chandax had been razed to the ground during the Byzantine siege and its coastal location made it vulnerable to pirate raids, so Nicephorus Phocas tried to move the capital a little further south, to Kanli Kastelli (modern Profitis Ilias), where he built a fort.

The people of Crete, however, did not agree that it was a good idea to abandon Heraklion and move to the interior, as maritime trade would decline, hitting the economy of the island hard. So the inhabitants quickly returned to coastal Heraklion and began to rebuild it. The harbour was improved and new walls were raised on the foundations of the Arab fortifications. In a very short space of time, Heraklion became an urban centre, the only city on Crete, and was named Megalo Kastro (Great Castle).

The administrative centre of the town was probably in the area of Eleftheriou Venizelou Square (the “Lions”). This development attracted a larger population and so the town, lying between the modern Dedalou, Chandakos, Epimenidou and Beaufort Streets, began to expand into suburbs.

Venetian Heraklion - Candia

The Fourth Crusade in 1204 resulted in the fall of Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire to the Crusaders. Alexius IV Angelus, the scheming usurper of the throne, ceded Crete to the leader of the Crusaders, Boniface of Montferrat, who sold the island in his turn to Dandolo, the Doge of Venice. The Venetians delayed the distribution of land, giving the Genoese pirate Enrico Pescatore the opportunity to occupy the island and even build 14 fortresses on it.

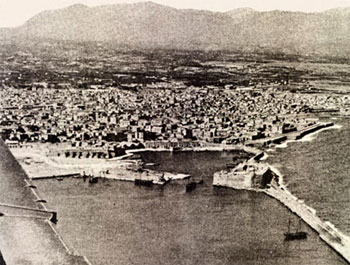

After a series of claims and counterclaims, Crete finally passed into Venetian hands in 1211. Their rule was to last until 1669, with Crete forming a single administrative province known as the Kingdom of Crete (Regno di Candia). Candia was the name of both the island and its capital (Heraklion), which remained the political, military, commercial, social and intellectual centre of the island throughout the five centuries of Venetian rule, and one of the most important urban centres of the Eastern Mediterranean.

Candia gained the reputation of “first city after the first city” of the Venetian Republic, meaning that it was second only to Venice itself. The front of the church of S. Maria in Venice bears a relief depicting the walls of Candia, the harbour with its shipyards and the fortress of Koules, the Voltone Gate, and city churches, monuments and fountains.

For the first two centuries following the Venetian occupation, the local population, rallying round the descendants of great families with local power and a strong national conscience, rose in a constant series of failed rebellions against the foreign yoke. Relations between the Venetians and the Cretans improved after the 14th century, as the latter gained more economic and religious rights and freedom.

The economic prosperity of Crete in general and its capital Candia in particular, led to a rise in living standards and the development of a refined Veneto-Cretan urban society. Fertile interactions between Byzantine and Italian thought produced what is now known as the Cretan Renaissance of the Arts and Letters in the 16th century. Painting, literature, poetry and theatre flourished with major works and representatives, creating a culture with Cretan features.

From the very beginning of their rule, the Venetians attempted to consolidate their grip on the island by introducing elements of their metropolis, Venice, to their new colony. This is most obvious in the architecture, with both the public buildings of Heraklion (Ducal Palace, Loggia, Basilica of St Mark) and private residences presenting distinctive Renaissance elements and a sense of grandeur.

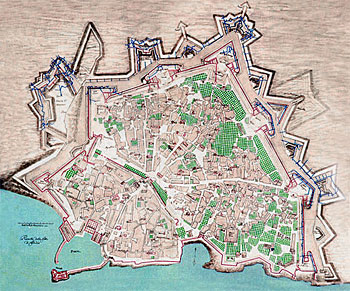

During the final two centuries of Venetian rule, Heraklion had almost tripled in size and the Turkish threat had begun to appear on the horizon. In 1462 the Venetian Senate decided to build a new fortified enceinte around the city, including the new suburbs beyond the old walls, and to reinforce the harbour installations. In the context of this ambitious programme, Candia was fortified according to the principles of the “fronte bastionato”, the bastion front system, becoming the only example of its kind in the whole Mediterranean to be preserved in such good condition today.

Most of the monuments still standing in Heraklion today date to this period, when the city was the most important harbour in the Eastern Mediterranean.

It should be noted, of course, that they were built using forced labour, as such works would not have been possible without the necessary manpower. The local male population up to the age of 60 was obliged to labour on public works for approximately two months in every year.

Siege and fall of Heraklion to the Turks

The fears of a Turkish invasion soon proved justified. In 1645 began the fifth Veneto-Turkish war. A Turkish army landed in west Crete in that year, and after many hard battles the Turks became lords of the whole island excluding Chandax (Heraklion).

The siege of Chadax by Turks

The siege of Chandax began in 1647 and lasted for 22 years, until 1669, when the city finally fell to the Turks following the betrayal of the Veneto-Cretan Andrea Barozzi. Barozzi was an engineer who gave the plans of the walls, showing their weakest points, to the leader of the besiegers, the Grand Vizier Köprülü Ahmet Pasha, in 1667. The defenders of the city were exhausted after 20 years of siege, but Heraklion held out for two more years until its final, conditional surrender (1669). The strongest fortress of the Eastern Mediterranean had withstood the longest siege in history.

The cost of the war in life and property was unprecedented. After the surrender of Heraklion, Köprülü Pasha demolished part of the walls for his triumphal entry into a ruined city. Only a few houses in the centre of the old town were still habitable but the rest had been wrecked by cannon shot, while the streets were strewn with ball and shot, masonry from ruined houses and many bodies.

The Turks immediately began rebuilding the city. It became the seat of the “Secretary of the Porte”, roughly equivalent to a governor appointed by the Sultan. The Venetian public buildings were restored to house the various government departments, while most of the churches were converted into mosques. The time that followed was one of cultural and economic decay, while the local populace rose in constant revolt, fighting for freedom and later for union with Greece.

It was not until the 18th century that historical circumstances favored the participation of the ever-increasing Cretan population in commerce, leading to the gradual development of Chandax.

In 1851 Chania became the capital of Crete, but this did not affect the economic and commercial prosperity of Heraklion, as the city was renamed in the early 19th century. Heraklion was levelled by a terrible earthquake in 1856. It was rebuilt as a large Turkish town, a typical Balkan city of mosques and minarets, coffee-shops, fountains, public baths, narrow alleys and tower-like houses with projecting upper stories.

At the same time Neoclassical styles appeared, charged with national significance, which to local people expressed the rebirth of the nation. Neoclassicism was also adopted by Turkish diplomacy as a modernizing feature.

Union of Crete with Greece - Heraklion in the 20th century

The Greeks from Asia Minor refugees in Heraklion

In December 1913 the union of Crete with Greece was officially proclaimed. Crete was now an inseparable part of the Greek state, sharing its adventures and its future. The Asia Minor Catastrophe of 1922 led to the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. A million Greeks from Asia Minor (the west coast of Turkey) and East Thrace came to Greece, while half a million Muslims left the country.

The last Muslim inhabitants of Heraklion (numbering 23,821) were forced to leave the city. Their place was taken by thousands of refugees from Asia Minor. The population increased rapidly and new suburbs, such as Nea Alikarnassos, Tria Pefka, Katsambas and Patelles were added to the city.

The changes in people’s daily lives were also impressive. The harbour expanded, the cars in the streets increased and the city acquired an airport. Concrete, electricity, the radio and the telephone “invaded” daily life in Heraklion, changing the habits and practices of centuries.

Unfortunately, during this period many monuments were thoughtlessly sacrificed on the altar of modernisation, either to wipe out unpleasant memories or for short-sighted financial gain. Any monument in Heraklion reminiscent of the Turkish past disappeared, being considered unsuitable for a modern European city. There were even plans to demolish the Venetian walls in order to allow the city to expand freely, but luckily this was considered too expensive and the plans were quickly abandoned.

Heraklion during the German Occupation

On the eve of the Second World War, Heraklion presented the image of a growing urban centre with intense commercial and maritime activity and a lively social life.

On 28 October 1940 the Greek-Italian War was declared, while the Germans invaded Greece in April 1941. Crete was virtually defenseless, as the Cretan soldiers were trapped on the mainland and could not get back in time to meet the German invasion of the island. The famous Battle of Crete began on 20 May 1941.

Heraklion was bombed by the Luftwaffe from 14 May onwards. As the day of the invasion approached, the bombing intensified and many inhabitants left Heraklion to seek refuge in the villages.

On 20 May thousands of enemy paratroopers were dropped over Crete. The island was defended by small Allied units (British, New Zealand and Australian) and the unarmed Cretans, who did not hesitate to face the fully-armed Germans with sticks and agricultural implements. The attacks were beaten off and the German parachute regiments suffered huge losses.

On 23 May, German bombers unleashed a violent attack on the whole city of Heraklion. Their targets were not only military installations but any building at all. At the end of the bombardment, a third of the city lay in ruins, with terrible loss of life. This day remained engraved on the inhabitants’ memory as “Black Friday”.

Between 28 May and 1 June the Allied troops withdrew from Heraklion and the city was surrendered to the Germans.

During the Occupation, Heraklion, like the whole of Crete, was a hotbed of resistance. The activities of the resistance organizations infuriated the Germans, who carried out numerous reprisals against the civilian population, razing whole villages to the ground. Among the worst incidents were the destruction of Anoyia and the Viannos holocaust.

On the night of 13 to 14 June 1942, a party of six saboteurs landed on Crete from the Greek submarine Triton, entered the area of the airport and destroyed about 20 Luftwaffe aircraft using incendiary bombs. Only two of the saboteurs - the British George Jellicoe and the Greek Kostis Petrakis - managed to escape, while one Frenchman was killed and the other three taken prisoner.

The next day, 14 June, the forces of occupation executed 50 inhabitants of the wider Heraklion area in reprisal for the sabotage. A few days earlier, on 3 July, the Germans had executed another 12 Heraklion citizens, including the mayor Minas Georgiadis and his brothers. The Avenue of the 62 Martyrs in Heraklion was named in honour of the fallen.

On 11 October 1944 the longed-for day of liberation of Heraklion arrived. The atmosphere in the city was tense, as the last Germans left with the curses of the crowd and the resistance fighters who entered the city. However, as soon as the German rearguard, accompanied by Allied officers, passed through the Chania Gate and drew away, all the onlookers broke into songs and cheers